Last autumn, I spent a weekend upstate in Schoharie County with a group of close friends. We partook in all the revelries a weekend upstate tends to offer: hiking, antiquing, s’mores by the fire. On Sunday morning, my friend’s brother, who was hosting us, came in from the woods with a freshly foraged bundle of yellow chanterelle mushrooms. He fried them up on the stovetop and shared how he’d been learning about edible fungi through the New York Mycological Society.

A society that teaches you to find snacks in your natural surroundings? Spending time in nature while picking up a handy apocalypse survival skill? I was intrigued.

A bit of internet research and $20 later, I became an official member of the NYMS. I signed up for the very next event they were hosting: a mushroom walk in Brooklyn’s Green-Wood Cemetery. A few days beforehand, the event was refashioned into a lichen walk due to drought-like conditions in the preceding weeks that had erased all signs of mushrooms. Unlike the finicky mushroom (which is just the fruiting body of a fungus, most of which is underneath the soil and therefore goes unseen), lichens are always visible rain or shine.

The walk took place on an unseasonably balmy morning in late October. A gaggle of eager amateur mycologists gathered in Sunset Park beneath the Gothic spires at the entrance to the cemetery. We wandered through the cemetery’s sprawling acres, guided by our fearless leader Wilton Rao. He had an incredible eye for lichens, effortlessly spotting small green patches of it on tombstones I would’ve passed by without a second glance.

Lichens are a mutualistic partnership between fungi and algae. As Wilton explained, “These are communities of two or three or more completely different organisms. You have completely unrelated living things that depend on each other for their survival. And this little community is called a lichen.”

In this community, fungi provide the structure and protection. They form the lichen’s body and help retain water and nutrients. Algae, or cyanobacteria, are the photosynthetic partners, producing food through photosynthesis and fixing nitrogen (meaning, they convert nitrogen gas from the air into a biologically usable form, thereby making an essential element available for plants and other life forms).

“The fungus provides the home and the algae provides the food,” Wilton said. “They are unrelated on the tree of life, they belong to two different kingdoms, and they cannot exist without one another. I find that utterly fascinating.”

Faithful readers may have noticed by now that I, too, love a good symbiotic interspecies relationship.

“Traditionally, evolution is a survival of the fittest narrative where every species is looking out for itself and the losers will die out and the winners will succeed. That’s not actually how life works. There are a lot of these symbiotic relationships where two different species depend on each other. We need each other, and lichens open a really interesting window into studying that.”

Cemeteries, it turns out, are living museums full of such windows. Lichens are abundant there because tombstones provide them with an ideal environment. Typically made of stones like granite, marble, or limestone, tombstones offer a stable and long-lasting surface where lichens can anchor. Some lichens can also extract minerals from the stone, allowing their homes to double as a nutrient source. Moreover, tombstones are usually exposed to plenty of sunlight, rain, and air — all the essentials that lichens need to thrive.

Weaving their intricate tapestries across these solemn sanctuaries of remembrance, lichens tell us: amid death, there is life.

Humble Little Things

Anyways, back to Wilton. An engineer by day, he moonlights as a citizen scientist and NYMS’s resident lichenologist. Originally from Hong Kong, he has lived in NYC for over 20 years, where he’s taken to strolling through local parks and figuring out which lichens call them home. After the Green-Wood walk, I caught up with Wilton to find out what sparked his passion for lichens.

“I think I’m just interested in weird, humble little things that nobody pays attention to,” Wilton shared. “Part of it is just the hipster in me saying, ‘Oh my god, nobody else cares. Maybe I should care.’ One day I woke up and realized I know almost nothing of this vast hidden world around me. These millions of species that have existed on this planet for millions of years and I just walk by them every day.”

Throughout those millions of years, lichens have proved extremely resilient. They can survive in some of the most inhospitable places on the planet, including deserts, Arctic tundras, and even the outside of the International Space Station, where lichens carried on photosynthesizing despite the lack of water, extreme temperatures, and full onslaught of radiation and ultraviolet rays from the sun.

“You have birds and trees and flowers. Among the least noticed groups are lichens. They just look like paint blotches on rocks and trees. Most people live their whole lives without noticing what they are. But once it clicks, you start seeing them everywhere and realizing there are layers of this world you knew nothing about.”

As someone who generally takes pride in my observational skills, I was humbled by this news of entire layers of the world I knew nothing about. But my bruised ego recovered in time to appreciate the many life lessons lichens teach us:

Collaboration yields better results than individuals can achieve on their own.

Don’t underestimate the little guy, who may be the toughest of us all.

There’s more to every situation than meets the eye.

And lest we still doubt the power of the humble lichen, consider that amid declining populations of many plant and animal species, lichens are now far more abundant in NYC than they were a few decades ago.

“Today, there are over 100 lichen species in NYC. In the 1960s, it was less than half of that,” Wilton told me. The resurgence is primarily due to improved air quality. “Factory pollution, heavy agricultural use of pesticides, exhaust fumes... Since the 1960s, in a lot of major urban centers across the Western world, those conditions have gotten better. I would call that a success story. It’s a small glimmer of hope in this absolute soul-crushing mess that constitutes climate change in 2025.”

This flourishing leaves us all better off, given the important role lichens play in ecosystem health. Lichens are one of only a few living things that can directly fix atmospheric nitrogen, enriching the soil and benefiting nearby plants. Lichens also contribute to carbon sequestration by absorbing and storing carbon dioxide during photosynthesis. And their ability to survive in harsh environments makes lichens a critical food source for tundra dwellers like reindeer and caribou.

Fairytale Fungi

An environmental success story, a symbol of resilience, and a model for interspecies partnership. Given all these accolades, I was left wondering why lichens seldom find themselves in the limelight and what we can do to elevate these tiny unsung heroes.

Part of the New York Mycological Society’s mission is to galvanize public interest in and knowledge of fungi around New York City and beyond. So I reached out to Sigrid Jakob, president of the NYMS, to better understand how that mission unfolds.

Sigrid is a self-taught mycologist whose resume includes everything from freelance marketing, to cleaning floors and toilets, to serving as a DNA sequence validator for a community lab.

Growing up in rural Germany, Sigrid’s parents had a plant nursery and her father was a hunter. Her earliest memories are of her parents pushing her stroller through the forest and discussing what they saw.

“I was steeped in the forest, but understanding its relationships took longer,” she said. “I was a sullen teenager and thought whatever my parents were interested in was boring. But I remember seeing bizarre-looking fungi, like out of a fairytale. It looked like nothing on Earth. And that left a lasting impression. It took me a long time to understand how it’s all connected but I eventually got here.”

Sigrid brought the fairytale to life by introducing some of the main characters in the fungi kingdom: the thieves, the composters, and the loyal collaborators. Their lifestyles are as follows:

Stealing: Some fungi infect plants, animals, or even other fungi. While some parasitic fungi can be harmful (e.g., rusts and blights affecting crops), others help with population control and maintain ecological balance.

Recycling: Mushrooms break down dead organic matter like fallen leaves, wood, and even animal remains, recycling nutrients back into the soil. Without these natural composters, ecosystems would be buried under layers of un-decomposed material, and essential nutrients would remain locked away rather than being made available for new life.

Partnering: Many mushrooms form mutualistic relationships with plants, particularly trees, through mycorrhizal networks. These fungi extend their branching filaments into plant roots, helping trees absorb water and nutrients while receiving sugars in return. This underground exchange — the Wood Wide Web — enhances forest health and resilience.

Microorganisms, Macro Discoveries

Sigrid calls her community of “interesting, strange, quirky, passionate” citizen mycologists the microsophere, and since joining, she has discovered hundreds of new types of fungi. If you’re surprised that this many species remain undiscovered, consider that among an estimated four million total fungi species, just about 150,000 have been described by science.

We humans have only scratched the surface of nature’s grand designs, and each of us has the power to peel back the layers of the unknown if we allow our curiosity to take us there.

For Sigrid, that curiosity led to learning how to use microscopes, read scientific papers, and photograph and document unidentified species on citizen science platforms like iNaturalist. While she has documented many unknown fungi, formally describing a new species requires publishing a scientific paper. Last year, she fulfilled a lifelong dream by doing so, based on her discovery of a new fungal species (Sporormiella tela) that grows on the dung of Canadian geese.

Graveyards and goose poop. Let’s add to our list of fungi-derived life lessons that sometimes the greatest wonders bloom in the unlikeliest of places.

A Historical Note

Tying her varied interests together is a love for storytelling, which Sigrid views as a crucial part of conservation. Among her eclectic array of accomplishments, Sigrid earned a master’s degree in fine art, with a specialization in photography, so weaving narratives comes naturally to her. “Studying mycology is also studying the history of science, the history of women in science, and many of the social evolutions that had to take place to get us to our current understanding of the world,” she shared.

“Hundreds of years ago, gathering was women’s work. So women were the first mycologists — though not with that title. There were some women who did amazing work in the early 19th century. The first people who founded and joined mushroom clubs were women in the late 19th century. It was an excuse for them to go out into the world using novel tools like bicycles and to be in nature by themselves. Women going out by themselves at all was frowned upon. But going out as part of a mushroom club was permitted. So it attracted a lot of women who wanted more freedom. It’s interesting to me as a pathway for liberation.”

Mycology took a turn at the beginning of the 20th century: “It became professionalized, and women got pushed out because you had to have a degree, you had to have formalized education. That persisted for many, many decades.”

[As an aside, this pattern has occurred across many fields as they become more prestigious, lucrative, and either implicitly or explicitly exclusionary to women. Computer programming is an oft-cited example. In the early 20th century and through the 1960s, programming was considered “women’s work”, but as computing gained prestige, the field professionalized and universities introduced formal computer science degrees, which were overwhelmingly male-dominated. As hiring and retention practices took root, the gender gap widened. I was also intrigued while recently reading about the reverse phenomenon, by which men systematically withdraw from spaces as women become the majority. This has occurred in disciplines like veterinary schools, biology, interior design, and teaching, and may help account for dropping rates of men enrolling in college. Unlike the symbiotic fungi, we humans seem to have a way’s to go in learning that different beings can thrive side by side, each bringing strengths that enrich the whole. The most enduring ecosystems, after all, are built on balance, not domination.]

Today’s fungi feminists, however, can celebrate that mycology has achieved a more even gender balance in recent years, as interest, cultivation, and commercialization of mushrooms have surged across diverse segments of society.

Sigrid explains that these “shroom booms” happen every few decades, and we’re on the tail end of the most recent one: “It coincided with the pandemic, partly because everyone was going out in nature when it was the only thing you could do. People realized there was all this amazing stuff going on in the forests.”

Other manifestations of the shroom boom include innovations in mycelium-based packaging, textiles, and building materials; increased research into the psychedelic and therapeutic properties of mushrooms; and the resurgence of mushroom lamps, which I noticed popping up in video tours of trendy apartments on my Instagram feed and then dominating my occasional (…or more than occasional) scrollings through Facebook Marketplace.

In the media world, 2019 saw the release of Fantastic Fungi, a film about “the magical, mysterious, and medicinal world of fungi” that captured the hearts of many. In 2023, our lockdown-hardened world got The Last Of Us, a post-apocalyptic television series set twenty years into a pandemic caused by a mass fungal infection.

Mushroom-inspired startups popped up, too. Society for the Protection of Underground Networks (SPUN) launched in 2021 to map fungal networks and advocate for their protection. Funga, also founded in 2021, combines modern DNA sequencing and machine learning technology to put the right native fungi in the right places, thereby improving forestry outcomes and enhancing microbial biodiversity. Mycocycle’s nature-inspired biotechnology came onto the scene a few years earlier in 2018, harnessing the recycling powers of mushrooms to transform waste into new raw materials. And then there’s the recent explosion of mushroom-based alternative protein brands.

Sigrid believes this mushroom mania has reached a saturation point. While there will be some natural outflow, a foundational curiosity has become firmly rooted.

“The people who were really interested stuck with it,” says Sigrid.

Beyond Foraging

Foraging is often the gateway to a broader interest in mycology, but there are many other dimensions to consider. Wilton eloquently made the case for fungi as a window into the interconnectedness of all living things, an invitation to consider our role in the wild, wonderful unfolding of the mysteries of the universe:

“170 million years ago when dinosaurs were still roaming the Earth, there were lichens looking like shrubby forks of cartilage coming out of the trees. We also found a bug with a lacewing that looks exactly like a lichen. 170 million years ago this bug was mimicking the lichen. There was already this ancient mimicry by which nature has designed the patterning of this bug’s wings to look exactly like lichen. 170 million years ago we have this example of how everything is connected, how the system of evolution can create these incredible forms. Something about that strikes me as so much more fundamentally beautiful than just looking at something and asking, ‘how can I eat this?’”

The joy of foraging for wild mushrooms and dining on the fruits of that labor isn’t going anywhere for mycologists, budding and seasoned alike. But I do love this invitation to peel back another layer. To consider the importance of each lichen, each mushroom, each of us — and the ecosystems we form part of and by which we are formed. The beauty of this exploration is that there will always be another (tomb)stone to turn over.

Interviewee’s Choice

This new feature in Natural Attractions will record interviewees’ responses to the question: What’s your favorite natural attraction? This could be a biome, a specific place in nature you’ve visited, a natural phenomenon, or any other interpretation of what “natural attractions” mean to you. In aggregate, I hope these responses become a travel guide of sorts, a chronicle of natural spectacles around the world.

Here’s what this issue’s subjects had to say:

Sigrid: New Zealand’s South Island! I was there for the first time last year. It’s like Disneyland for plants and animals and fungi. The biodiversity is insane, and the intensity of relationships between everything — it’s in another league. It’s the most awesome and humbling thing to see this undisturbed biodiversity that’s been left alone for the most part.

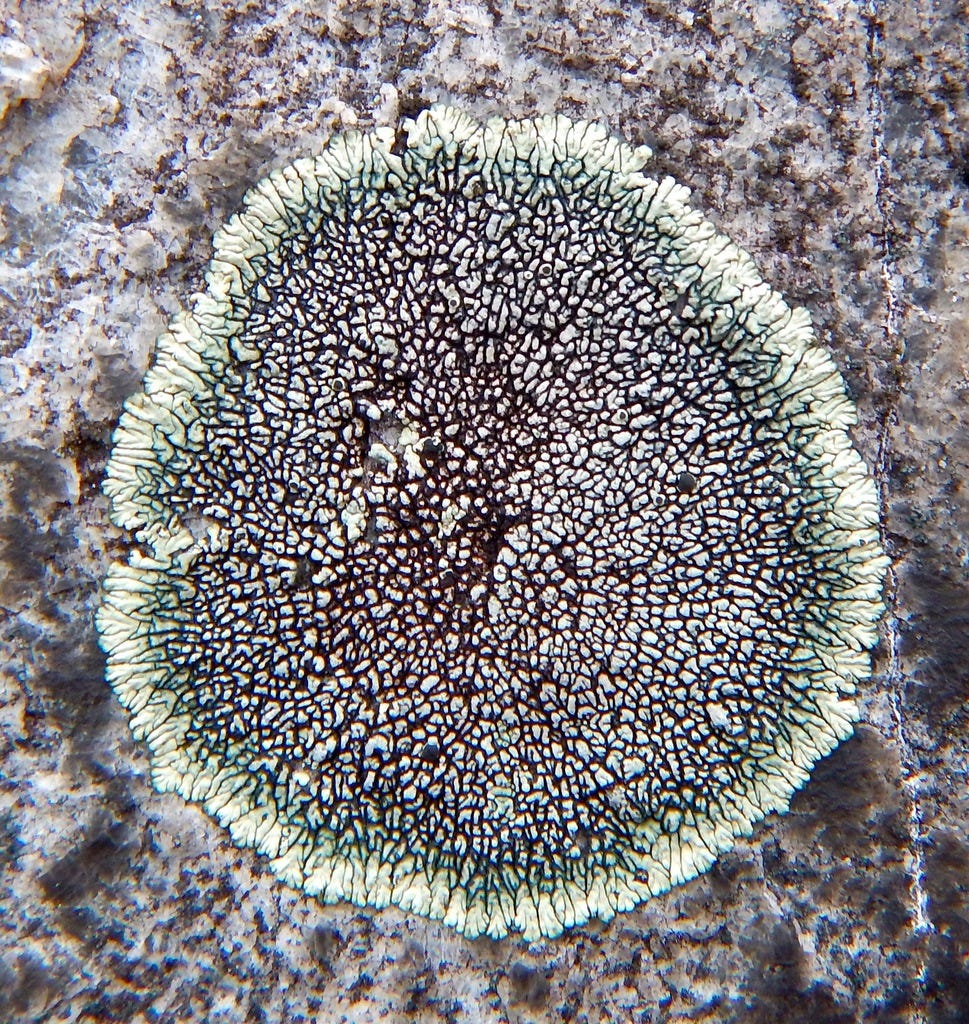

Wilton: I’ll give you my favorite lichen, because that would be my favorite natural attraction. There’s one called the golden moonglow lichen (Dimelaena oreina). It’s stunning. It looks like a starburst and it’s got this incredible color that’s hard to describe. It’s a pale yellowish greenish color — like a moonglow. You have to see it in person, it’s incredible.

On a Different but Related Note

Something I enjoy about cemeteries is reading the gravestones and feeling touched by the love shared between strangers I’ll never meet. It’s one of those experiences that makes me feel my humanity in its most vivid colors.

I’ve discovered you can also enjoy this experience in NYC’s parks, where benches are dedicated not just to memorialize the dearly departed, but for all manner of occasions, such as birthdays:

Or anniversaries:

Or declarations of love:

Or marriage proposals:

Or listing all your favorite things:

Or philosophizing on life:

Or simply laying claim to a really great bench:

10/10 recommend strolling down bench-lined pathways and letting the ensuing waterfall of emotions tumble out. Tell me, dear readers, what would you put on your plaque? To whom and to what would it be dedicated?

Correction:

In the last issue, I erroneously mentioned the 10+ native honeybee species at Boquete Bees & Butterflies, when I should have written: “10+ honey bee species…” An eagle-eyed reader, my elder brother Naftali and newly appointed fact-checker of this newsletter, pointed out that there are fewer than 10 honeybee species globally and that a honeybee is quite different from a honey bee. He was gracious enough to write out the following correction, for other truth seekers in the audience:

“The word honeybee was corrected to honey bee, as the former is technically incorrect, representing the more well-known honey-producing bees of the genus Apis whereas the article refers to honey-producing bees, of the less familiar but closely related stingless honey bees. Producing honey with honeybees is called apiculture; whereas producing honey with stingless honey bees is called meliponiculture, which has been practiced in the Neotropics for centuries.”

Thank you Naftali!

The Last Word

“Neither tales of progress nor of ruin tell us how to think about collaborative survival. It is time to pay attention to mushroom picking. Not that this will save us — but it might open our imaginations.”

― Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins

Intergalactic lichen! Loved this, especially Bob’s bench 😂